How a Duke Professor and Two Duke Ph.D.s are Building an AI Drug Discovery Start-Up

If you’ve met Duke University Professor Bruce Donald, you know he is passionate about computer science and its applications. Heck, you may have even read one of his five books on topics including robotics, artificial intelligence, and most recently, computational biology.

What you may not know is how wide-ranging Donald’s interests are, how he got into the field, or how his entrepreneurial spirit has blossomed into promising start-up Ten63 Therapeutics, a Duke spinout and Duke Capital Partners portfolio company which recently closed a Series A round of funding. This is the story of Donald’s journey: how he is working with his former students and tapping Duke resources to bring groundbreaking innovations to market.

Encoding success early

Bruce Donald was nervous.

The year was 1982 and he was less than two years out of undergrad, sitting across from the Director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) Laboratory, Professor Patrick Winston.

Donald had applied to the Ph.D. program in MIT’s computer science department with plenty of experience in computation: from taking early coding classes taught by MIT undergrads to working in a computer store doing systems programming for early personal computers.

Crucially, Donald had worked for six years in the Harvard Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis. There, he had been part of a pioneering group of scientists pushing the boundaries of cartography and architectural design using computers and contributing to the foundations of modern Geographic Information System (GIS) programs.

What he lacked, however, was the usual formal education – Donald had graduated from Yale University with a degree in Russian, choosing that field over his other interest of math in no small part because the math classes met every weekday at 8AM while advanced Russian met in the evenings once every other week.

“We’re a little concerned about how to fund you,” Donald recalls Winston telling him. “You do have an unusual background.”

So, here he was, in the director’s office, highlighting his bootstrapped bona-fides – the strangeness of the whole experience heightened by the fact that the student and the professor happened to be wearing the same outfit.

“Tan Wallabees, khaki pants, a blue Brooks Brothers shirt, and a camel sweater,” Donald said. “He thought that was very strange, but it was totally accidental.”

Donald acknowledged his “strange background” but kept insisting to Winston that he would be a good candidate, even offering to pay the graduate school tuition with money saved up from his various jobs.

“He looked at me with a long pause and one of those long stares that technical people give you when they think you’re being an idiot, and he said: ‘Thank you. Please never say that again to MIT. We pay for everybody to be here, it’s just a question of which group,’” Donald remembers with a chuckle.

Donald was accepted into the MIT program and graduated in under five years with a Ph.D. in computer science, continuing his research on spatial planning and computational geometry. Honing his expertise, he started seeing how his unique way of working with computers in 3D space could be applied to more fields, such as designing molecules.

“I had the bug,” Donald said. “I wanted to be a computer scientist.”

What followed was successfully winning tenure at Cornell University, then a sabbatical at Stanford University, enabling start-ups and working at Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s incubator Interval Research Corporation, then a return to academia at Dartmouth College.

In 2006, Donald joined Duke University. Even with all that formal training in computer science under his belt, Donald still relishes getting his hands dirty in various fields.

His Duke appointments as a Professor in the departments of Computer Science, Mathematics, Chemistry, and Biochemistry highlight his growing interest in applying computational techniques to design new molecules.

“I’m really an applied mathematician,” Donald said. “I try to use math to solve hard problems in robotics, in computational chemistry, and in biology.”

Wiring up a Duke network

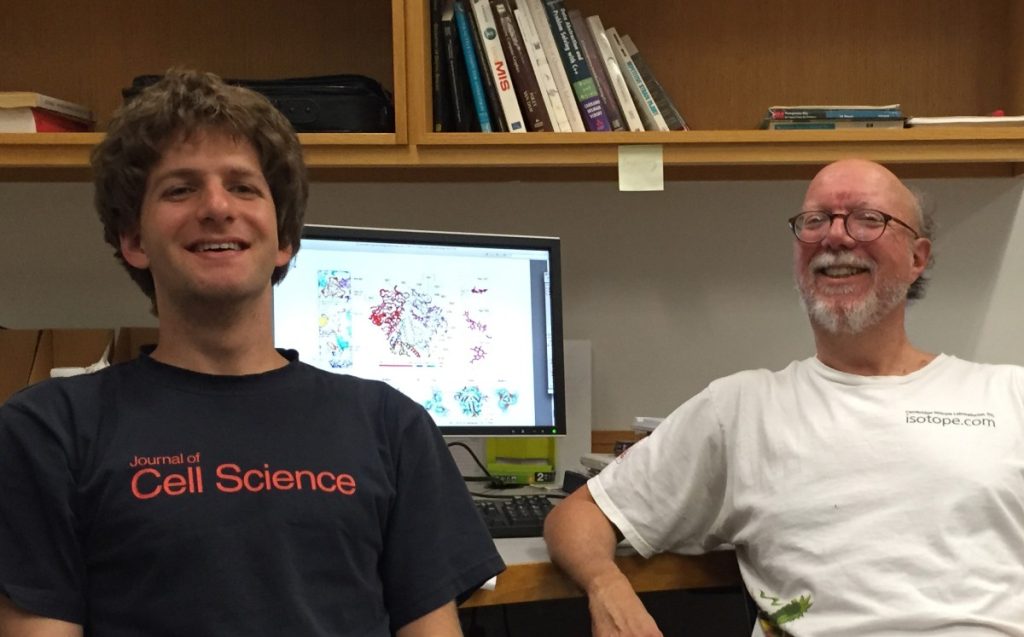

“For ten years, I have been asking my students: ‘Look, we have this software, do you want to start a company?’” Donald said. Eventually, two of his Duke graduate students – Marcel Frenkel and Mark Hallen – jumped on the opportunity and founded a start-up in 2018 now known as Ten63 Therapeutics.

“Bruce welcomed me in during a very difficult time of my life,” Frenkel said. “My mom had just been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and I was looking at what technologies could possibly help us fight back. Bruce immediately saw how we could collaborate on what they were developing.”

“With Marcel in the picture, the business side has improved considerably,” Hallen said. “And Bruce has this ability to do really rigorous science across a vast array of disciplines. He’s helped me tremendously to grow as a scientist.”

In molecular biology, as the dictum goes, structure equals function – and creating new drugs is an exercise in designing a molecular structure that interacts with a target structure in a particular, puzzle-piece-fitting way. Ten63’s software is a complex assortment of interlocking algorithms that work together to propose molecular structures that should interact well with a given biological target.

The difficulty is that the options are almost limitless. The name Ten63 is a play on 10 to the power of 63, or one followed by sixty-three zeros – a back-of-the-napkin estimate for the number of possible small molecules with drug-like properties. The trick to finding new, exciting drug designs is to explore the greatest number of possible options while also having a way to then rank their predicted effectiveness.

“It’s a combinatorial optimization problem,” Donald said. “The kind of tricks that are in the algorithm are combining geometry of the structure, detailed energy fields, quantum mechanics – lots of approximations.”

Scaling up the circuit

Though the entrepreneurial streak was strong in Donald, starting a company around software chafed a bit against his values of transparent research collaboration.

“I’m a big open source guy,” Donald said, “but Dinesh said: ‘I know what you need, you need a dual license.’”

Dinesh Divakaran, former Director of Digital Innovations at the Duke University Office for Translation & Commercialization, worked with Donald to balance his desire for continued transparent sharing of the software for research purposes with the necessity of protecting intellectual property in order to accelerate the application of the work through a company and to make it more attractive to industry partners. Divakaran also took the time to explain the dual license arrangement to potential investors.

So, the split was made. Donald’s Duke lab uses an open source version of the software, OSPREY, to work on computational and experimental challenges in protein design, which has led to about two dozen clinical trials of designed drugs like antibodies and vaccines. Ten63 Therapeutics then builds on the OSPREY foundation to create a proprietary platform used to design small molecule drugs.

One of the key innovations is shifting from designing molecules with atoms arranged only in discrete, rigid ways to allowing for more freedom of placement and fluid conformations. Playing in this larger sandbox requires the help of artificial intelligence to cull through the massive search space.

Using their unique AI approaches, the lab and company can also design drugs to head off possible resistance that diseases may develop. This is a massive problem in healthcare – for example, an often-cited figure in cancer research is that over 90% of deaths in cancer patients are due to multidrug resistance.

“We’ve been able to actually predict the resistance that will emerge in some of these systems even before preclinical studies,” Donald said. “This is a huge advantage.”

The team was excited by their potential but knew they had a lot of work ahead, so they applied to the 2019 class of IndieBio, a leading start-up development program.

“They said: ‘This is great. This resistance stuff you’re doing is fabulous. We want you in the next class of companies,’” Donald said. “We said: ‘Great, we’re ready in the fall.’ They said: ‘No, we want you to come today.’”

Donald applauds how committed his co-founders were to the opportunity: two weeks later, Frenkel and Hallen were living in California to fully take advantage of the IndieBio program.

“These guys are very good,” Donald gushed. He commuted back and forth between the Bay Area and the Triangle to help.

“From day one, I realized what Bruce and Mark had been developing was this amazing technology and we had an opportunity to make a huge impact,” Frenkel said. “But it couldn’t be within academia, we had to move faster. The only way to do that was through industry.”

Generating the future of drug design

As the company grew, investors took note. Recently, Ten63 closed an oversubscribed $15.9 million Series A fundraise led by local VC Hatteras Venture Partners, joined by Morpheus Ventures, SOSV, Draper Associates, Alexandria Venture Investments, the Sigma Group and other new investors.

The science is progressing well: the company has disclosed it is focusing on two targets, c-Myc and KRas, both of which are often activated in stubbornly drug-resistant cancers.

“It’s amazing,” Donald said. “Our designed molecules are hitting these targets that were very difficult to hit before.”

With the new funding, Ten63 is accelerating its R&D efforts and has leased space in the Chesterfield building in Downtown Durham, setting up a wet lab space in the Triangle to complement their California offices. Hallen is looking forward to tapping into resources and network in the area, where the team already has strong connections to the universities, investors, and talent – and where Hallen grew up dreaming of maybe one day starting a company.

“It’s kind of a no-brainer to set up in the Triangle,” Hallen said. “I don’t think that there’s a better area for a company like ours.”

One of the things that excites Donald the most is the company’s foray into using generative AI – not only using machine learning to search possible structural space but enlisting AI to come up with new designs itself. The difficulty there is that generative AI systems do tend to hallucinate. The general public is getting a crash course in this in real time right now, with ChatGPT and similar large language model-based systems that have exploded into the mainstream knitting together falsehoods out of thin air, which are even tripping up lawyers.

“If you have the capability to test many things in the wet lab, you don’t mind if your algorithm is generating a lot of nonsense. I’m not interested in that,” Donald said. “I want to know what the algorithms are doing.”

By pairing generative AI with their existing optimization framework, Ten63 is trying to capture the best of both worlds: tapping the creative side of artificial intelligence while keeping it on track with the guardrails inherent in our most advanced models of how molecules interact.

Donald thinks this kind of approach is a more sustainable approach for drug design – and one that would be more effective in passing on his career passion of the entrepreneurial application of computer science.

“I am interested in the regime where the computational predictions are accurate, so you only have to test a handful of compounds to find some that work,” Donald said. “I think this will be the future of drug design.”

###

Learn more about innovation support and investment provided by Duke’s Office for Translation & Commercialization and Duke Capital Partners.